|

News of a supposed "Worldwide Food Glut" has made headlines.

Some think the danger of a population explosion is past!

Others say the population bomb is still relentlessly ticking away.

Is the world on the way to self-sufficiency?

The answer is in this article.

THERE is no starvation in India at all," announced the Indian Ambassador to the United States, Nawab Ali Yavar Jung. "There is no such thing as starvation in India," he continued. "Scarcity is an old-fashioned word because of our agricultural progress."

Ambassador Jung said his country expects to be self-sufficient in food production within a maximum of three years and to be exporting grain within five years.

Journalists who follow Ambassador Jung's thinking speak of a "global food glut" and "soaring surpluses."

A Different Story

At the same time, equally important officials of the Indian government say the opposite:

India's President Dr. Zakir Husain said, "I would like to caution against too much talk of an agricultural revolution. We are not free from the vagaries of monsoons. There are too many imponderables."

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization reported in 1968 that "it would be a mistake . . . to jump to the conclusion that the world's food problem has been solved, either temporarily or permanently."

Why the controversy?

It is time we looked at the facts!

The 1969 Wheat Crop

When scientists speak of the "food glut" they refer mainly to grain crops, and most commonly wheat, corn, and rice. Corn, or maize, is largely fed to livestock. Rice is usually consumed in the country where it is grown. So it is wheat that is usually the focal point of trade and commerce of food.

In 1967, 1968, and 1969, wheat crops were very good, especially in Western nations. The wheat crops of 1969 were very high in the United States, Russia, Australia, and Canada, but low in South America (especially the key nation of Argentina), in Asia, and Africa.

Asia's crop dropped by a million tons. Africa's crop increased slightly but produced only one-fourteenth as much as the Soviet Union alone! (These production statistics come from the FAO. They refer to 1969 spring harvest and the 1968 fall harvest)

|

|

The worldwide total for 1968-69 was an increase of 13 percent in wheat. According to early reports, the 1969 fall harvest of wheat is down only 7 percent from the 1968 fall total (Journal of Commerce, August 5, 1969).

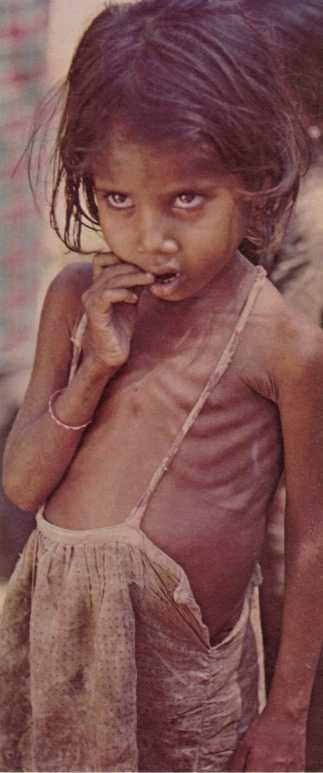

Thus we can look upon 1968-69 as a very good year for wheat. Maize and "miracle-rice" also had good years of production. This is very good news. But unfortunately, the good news ends here. The problem is that the "food glut" is not getting to the mouths of starving Africans, Asians, and South Americans.

There are six problems generated by the "Global Food Glut."

I. The "Food Glut" Causes Price Wars

Almost by definition, the food glut is a price war. Over-supply pushes food prices downward so that farmers cannot sell at a profit. Producing nations are locked in a price war, as they fight to get rid of their one-year over-supply.

For instance, wheat price per bushel has descended from $1.83 in 1967 to about $1.50 in 1969 in the United States. Some grades of wheat in the U.S. Southwest are bringing only $1.20. This cuts the farmer's profit margin to very little or nothing. The farmer then pushes for government support of the price. Most governments cannot afford this, and underdeveloped countries are not rich enough to buy at even the low price. Thus the farmers or governments hold on to the wheat and hope that the glut will go away the next year.

Meanwhile the wheat sits idly in storage. And while the food lies in storage, mildew, rats, and other infestations ruin one pound in every five. While the rats get fat, Asians and Africans starve. This brings us to problem number two.

II. "Food Glut" Isn't Feeding the Hungry

In all the plethora of articles on the food glut, you'll never read one about the "glutted" nations feeding the starving nations. The United States is the main country which has shipped a large tonnage of surplus to the hungry at low prices. And even that has declined recently.

The food is going to storage, while thousands starve. As one newspaper headline said, "Too Much Wheat — but Many Millions are Going Hungry."

Canada and Australia have surpluses, but they don't usually have large tonnages of surplus to sell at a loss or give away.

Russia, who grows more wheat than all North America, South America, Africa, and Australia combined, could easily feed India. Their surplus could feed the equivalent of three loaves of bread every week to every Indian — but they don't.

If nations can't get their profit, they'll keep the wheat. Meanwhile, very few Asians and Africans are being glutted by the "Food Glut."

III. STARCH, not PROTEIN

The constant reference to food surpluses usually dwells on wheat, corn, and rice. What most people don't realize is that the average Indian eats more calories of grain per day than the average American! Unfortunately, most of it is rice.

Proteins are a different story. According to the U.N. F.A.O. Production Yearbook, the average Indian eats 6 calories of meat per day, while the average American eats 600! The same Indian eats 1 calorie of eggs and 4 calories of fish, while the same American eats 70 and 25 calories, respectively. An American drinks three glasses of milk (about 400 calories) to the Indian's half-a-glass (about 80 calories) each day.

Thus, the American's animal protein intake is 1000% to 1200% greater than the Indian's. The average Indian consumes 6 pounds of meat a year, while many Americans eat that much in a week.

Grains make up 60 percent of the Indian diet (1150 calories), while they make up only 20 percent of the American diet (650 calories). Thus, even if the grain glut reached Asia, it would help their nutritional level very little; the starving millions need more complete proteins available only through meat or animal products.

It is easy to say India leads the world in livestock population. It is easy to say that the Indian Ocean is one of the richest fishing grounds in the world. But it is not easy to convince an Indian to alter his sincere religious beliefs to tap these protein rich sources.

IV. Crops Depend Heavily on WEATHER

The bumper crops of the last three years are unanimously attributed to exceptional weather: "The increase in food production [in 1968) was largely due to good weather." (The Daily Telegraph, September 13, 1968)

"A major reason for the glut is bumper crops resulting from good weather" (Time, Sept. 12, 1969, p. 90).

Weather is the major reason why nobody can predict famines or surpluses. Because one year or three years are blessed with good weather doesn't mean the following year will be good. Because monsoons may have been favorable for three years doesn't mean they cease their history of unpredictability.

Many scientists and authors have predicted the middle 1970's as the target date for famines. Among these are William and Paul Paddock, authors of Famine 1975 and Hungry Nations. In an interview with Rotarian Magazine, they admitted that weather is the key factor in predicting these dates.

"Luckily," they said, "these last two years have seen exceptionally fine weather throughout most of the agricultural world. As a result we may have a couple of years of extra grace before our prediction comes true.

"Of course, when crops are good," they added, "government officials take the credit by pointing to their excellent planning in providing fertilizer, improved seeds, financing, etc. When crops are poor, the same officials blame the low yields on bad weather.

"No, the big increase is due to the excellent weather God has given. . . . The fundamental problems on which we based our predictions remain unsolved. Although these advances may delay the day of reckoning, the real problem remains: the population explosion." (Rotarian Magazine, June, 1969, p. 17, emphasis ours)