|

Keystone, Bastin Photo

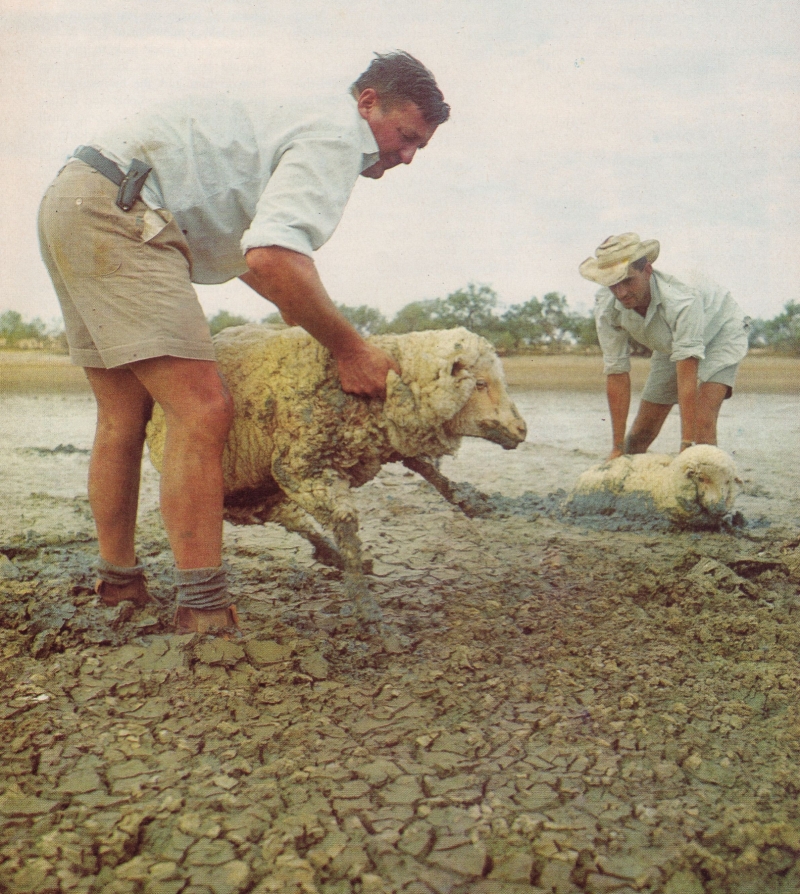

Bill McLauglin and John Glasson pull sheep out of mud in dry lake.

This station has lost 8,000 sheep out of 12,000 since 1964.

|

The PLAIN TRUTH Staff in Sydney, after a 1000-mile survey of some of the country's worst drought area,

reports what might become the most disastrous drought ever.

TO THE two and one-quarter million residents of the sprawling metropolis of Sydney the word DROUGHT means little. There is only the inconvenience of not being able to Wash the family car with a hose, or water the lawn except between 5 and 8 p.m.

But to the man on the land, drought takes on stark reality. Its specter is barren pastures, dried-up tanks and reservoirs, the stench of dead sheep and cattle, withering crops and blinding, choking clouds of dust.

What You Haven't Been Told

For seven long years Australia's vast Northern Territory has suffered drought, interrupted by occasional heavy flooding rains which do little apart from causing erosion. During this period the Territory's beef and cattle population has fallen by two thirds. Only within the past two months has normal soaking monsoonal rain fallen to give temporary relief.

But this is only the beginning!

More recently, New South Wales and Queensland, Australia's two primary producing states, have begun to suffer.

Between them the states of Queensland and New South Wales account for 45 percent of the nation's wheat crop, 55 percent of sheep population and wool production, 64 percent of the beef and dairy industry as well as 100 percent of sugar — all vital staples in the nation's economy.

The outcome of two years of severe drought in northwestern New South Wales and southwestern Queensland — as well as subnormal rainfalls over most of the remainder of these two states — has produced shocking results. At a time when hungry millions around the world are crying out for food, Australia, the world's third largest exporter of wheat, has experienced a 30 percent drop in wheat production over the bumper years 64-65. Production in New South Wales was cut by 110,000,000 bushels — a whopping 75 percent! The seriousness of this reduction becomes evident when it is realized that in normal times New South Wales produces nearly 40 percent of the nation's wheat.

|

Keystone, Bastin Photo

Starving stock for sale at Maitland yards during 1965 drought.

|

Even more alarming is the effect of two years' dry conditions on the sheep and wool industry. Although not finally determined, total sheep losses in New South Wales and Queensland are estimated at between ten and fifteen million. This loss takes on staggering proportions when it is realized it represents about half the 28 million sheep in all the U.S.A.

Exports Affected

Loss in wool production is presently estimated at about $70,000,000, representing a fall of 13 percent nationwide — 30 percent down for New South Wales and 25 percent for Queensland. Wool losses will become an even more critical factor in the Australian economy if the drought continues. As the world's leading producer of wool — the 1964 clip valued at over one billion dollars, 94 percent of which was exported — she can ill afford a continuation of the present drought.

The loss of beef and dairy cattle to New South Wales and Queensland is estimated at 1,000,000 head. This has dealt a serious blow to Australia's export beef market, which represents nearly one half the total production. Losses expected for 1965-66 are equal to more than one third of Australia's $176,000,000 beef export market. Overall production in New South Wales has fallen 22 percent. Butchers in the metropolitan area are finding it increasingly difficult to provide quality meat and prices have risen markedly.

In Queensland, grave fears are being expressed for this year's sugar crop, after failure of the wet season in North Queensland. Most sugar cane districts report only one half the normal seasonal rainfall. In 1964 there were 1,724, 000 tons of sugar produced. Of this, 1,116,000 tons worth $150,000,000 were exported.

|

Firsthand View

In order to assess the effects of the drought firsthand, members of The PLAIN TRUTH staff in Sydney toured 1000 miles of New South Wales' worst drought-affected area. Picking up a chartered twin-engine Piper Aztec at Dubbo, two hundred miles northwest of Sydney, we began the tour. The region around Dubbo, in the heart of the rich New South Wales wheat district, had recently received its first good rain in months. A very light cover of green was just beginning to show. We headed west from Dubbo toward the more recently stricken towns of Nyngan and Cobar, ninety and one-hundred-eighty miles distant. The green began rapidly to fade into barren reddish-gray soil, dotted by Mulga bush. Here and there wheat fields had been sown just after the rain by farmers hopeful that follow-up rain would produce the crop that failed last year.

Below lay the nearly dry Macquarie River which supplies water to Nyngan and Cobar, as well as the large copper mine at Cobar. Already the diminishing waters of the Macquarie have been the basis for a dispute between these towns, the copper mine and the agricultural interests along the river. Flow is regulated by the huge Burrendong Dam just southeast of Dubbo. Only recently completed — too late to catch the previous good wet years — the 1.3-million-acre-foot-capacity reservoir is only 2 percent full. It is so low that the little remaining water has to be pumped over the silt trap at the bottom of the outlet.

This district has already lost 55 percent of its sheep population, according to the best official estimates so far.

Many grazers have been completely wiped out. Others are hanging on with dogged determination, hopefully awaiting drought-breaking rains that have yet to come. Local residents at Cobar estimate that if rainfall resumed its normal 12 inches per year tomorrow, it would take a minimum of four to five years to build stock back to the pre-drought level. Losses to the grazers have in turn hurt the businessmen in towns like Nyngan, Cobar and Bourke (farther to the north). Some small merchants are carrying debts adding up to several hundred thousand dollars. To make matters worse, closure of the Cobar Copper Mines is imminent if substantial rains don't come soon.

A hundred miles west of Cobar we landed at a fifty-thousand-acre sheep station about fifteen miles east of the Darling River.

Two years ago this station (ranch, to Americans) had six thousand sheep. Now there are only five hundred left. Another 2500 are on the stock routes hundreds of miles away, following what food remains. Three thousand have died in the last two years. Without immediate rain there is little hope for the remaining five hundred sheep. Although six-tenths of an inch of rain fell just two weeks before our visit, there was absolutely no evidence of any results. The dusty yellow-red soil was completely devoid of grass. Wind erosion had begun to take its toll. Even the kangaroos and rabbits had died out.

At the homestead, placed near the long-since-dry creek bed running behind the main house, the owner's wife showed us a colored photograph taken four years ago. This same land, now barren except for scrub, was then covered with waist-high grass and wild flowers.

Now heading northeast, we followed the meandering Darling River 125 miles to Bourke. Most of this leg of the trip was through a dense cloud of dust extending above our 7000-foot cruising altitude. The Darling was now about half full, but a few months ago before freshening rains had fallen in Queensland; it had dried to a series of water-holes.

Circling Bourke, the last outpost of any size in northwestern New South Wales, we could see nothing but dry, parched land with the exception of a few green irrigated patches in the vicinity of the township. Ordinarily the entire region should have a grass cover at this time of year.

According to one local businessman, Bourke has never been as bad off financially as it is today. Although despairing hope is still held for this region, it will take years to recover even if good rains begin to fall. One of the more pitiful aspects of the drought is to be found in the Bourke hospital. It is packed with Aboriginal children suffering from malnutrition and virus diseases brought about by the lack of water and the dust in which their families have been trying to eke out an existence.

Governor's Visit

Leaving Bourke we traveled one hundred miles further northwest to a station near the Queensland border. Here again was the same dismal story, only worse. Stark tragedy is seen on every hand. With no rain of worth for two years, the owner of this station has lost 6000 out of 7000 sheep! The remaining thousand are living on the remnants of the sparse growth that came from light rains in December. Now that this is about gone there is little hope for the few remaining sheep. Red sand dunes begin to collect over the drying bones of their six thousand predecessors.

Here we learned that the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Roden Cutler, and his party from the New South Wales government and members of the press had preceded us by two days using this same aircraft. Having lunch at the station, the Governor had remarked to the owner and his wife that this area reminded him of the Libyan Desert. Surely no desert could be much worse, including the desert regions of southwestern United States. The unused stock pen stood in stark relief against the fifty thousand acres of utter desolation that surrounded it.

The scene exactly fit descriptions given long ago by divinely inspired prophets who are generally regarded as wild visionaries. But these conditions are real! Tragically real!

Leaving the ironically named "Hungerford" district behind, we headed east along the Queensland border. In the settlement of Enngonia 75 miles north of Bourke, we found destitute Aboriginal families trying to subsist on a diet of bread and jam, supplemented by whatever wild game — kangaroos, emus and lizards — might be found. Farther east the nearly empty Lake Narran could be seen down to the right. Never known to be dry, Lake Narran is at its lowest level in living memory.

Reservoir 91 Percent Empty

Changing course from east to southeast we began to approach the rich black plains of the Namoi River. In marked contrast to the dry-appearing plains below was the rich green checkerboard of the comparatively small Wee Waa irrigation district. American cotton farmers from the San Joaquin Valley in California began to come here about four years ago, to apply American mechanized cotton-growing techniques to the similar Australian conditions. These efforts brought startling results. This district now produces 75 percent of Australia's cotton crop. Vital to the success of the project, however, is the Keepit Dam about one hundred miles up the Namoi River not far from Tamworth. This dam controls a reservoir which provides the Namoi with its year-round flow of water for irrigation. Value of the 1965 cotton crop is placed at one million dollars.

But the Keepit Reservoir which held 300,000 acre-feet of water two years ago is now reduced to a mere 31,000 acre-feet — just 9 percent of its 345,000-acre-foot capacity. Without heavy rains there will be no water for next year's crop. Disputes are already arising over the allocation of what little Namoi water is left. A $65,000 rotary drilling rig has just been brought into the country from the United States in the hopes of drilling for water to relieve the expected dry spell.

Wheat Production Critical

The 150-mile trip back to Dubbo from Keepit Dam was through the heart of the New South Wales Wheat Belt. Silos towering above the small towns, recently filled to capacity, were now virtually empty. Seventy-five percent of the State's wheat crop failed — production 110,000,000 bushels short. This loss is equal to one half of last year's export wheat crop of 210,000,000 bushels. We now have that much less to help feed the hungry areas of the world. Instead of the twenty-five-bushels-per-acre yield reaped the preceding year, this area of New South Wales saw yields of from nothing to 2 or 6 bushels per acre.

Although much optimism is expressed over the prospects of a good wheat crop next season, this is strictly conjecture. No drought-breaking rains have yet fallen. None are seen in the predictable future. And in order to earn as many export dollars as possible, only about one third of one year's domestic supply of wheat is being carried over into next year. None is being saved as protection in case of worldwide famine. A few more successive disaster years like this could put Australia, the world's third largest wheat exporter, in the position of having to import wheat for her internal needs!

Will it be available then?

Disaster — Unless Rain Falls

After this tour, which encompassed and traversed approximately 100,000 square miles of one of Australia's major agricultural areas, one recognizes just how much man is dependent upon the weather for success.

An estimate of the financial loss from drought up to the present time is 800,000,000 dollars — the total of one year's defense budget in Australia. This figure includes not only the immediate 357,000,000-dollar loss in primary production and stock, but the price of restocking, the loss to railways, banks, lending institutions, machinery, equipment, manufacturers and distributors, the tax collector and value of shares (stock) in public companies associated with the agricultural sector. And as each month of this drought continues, the bill goes up. The situation in the irrigation areas has thus far been much brighter. However, with low rainfalls over the catchment areas, the irrigation districts are threatened for the coming year, as already noted, unless sufficient rain falls. The main storage dams and reservoirs in New South Wales at present contain from two percent of capacity up to no more than forty. In a Press release, 8 March 1966, Mr. Jack Beale, Minister for Conservation stated:

"The vast inland river system is slowly drying up. Unless substantial rains are received this autumn or winter, several of the main dams in the state will, by the end of September, be so dry that they will be unable to provide water even for stock and domestic purposes. This could occur despite the present restrictions on irrigation and the intention to suspend irrigation on certain affected river systems in stages from now on until 30th April.

"The long drought, which first attacked over the broad acres of the State where production is dependent upon rainfall, has caused such heavy losses, it is now attacking us in the catchments of our river systems.

"The hard core of reliable production based on irrigation, which already has been restricted, is now threatened with extinction.

"Some towns, mines, and industries are facing a serious situation."

For a nation such as Australia, whose economy relies on the weather for 75 percent of her total exports, the seriousness of drought takes on major proportions. The 357,000,000-dollar loss estimated for this year will be nothing to that which will follow unless the present trend halts.

Why Drought?

Many people are asking this question. The man on the land blames lack of foresight and bad planning by the government. The government says that abuse of the land arising from poor management, overstocking, and wanting to squeeze every bit of available profit from the land in good years is responsible for the present conditions. Both are partly correct.

But what man does not seem to realize, is that he does not control the weather. The reason for the drought is our going the way that seems right to man and breaking every physical and spiritual law which governs our wellbeing (Prov. 14:12). The only way Australia as a nation can be sure of the right weather is to turn from the way that she is presently going and wholeheartedly serve God. Unless Australia repents she can look forward to ever-worsening conditions which will ultimately bring her to her knees. Read it in your own Bible. Compare Deuteronomy 28 with Leviticus 26:3-4, 18-20. Nationwide repentance would bring rain. That is God's promise. But who wants to repent?

This is a lesson for the whole English-speaking world. If you do not know the startling truth of where our people are mentioned in Bible prophecy, write immediately for our free booklet, The United States and the British Commonwealth in Prophecy. Unless our people repent bitterly and are willing to learn from what is now happening in this country, our people will perish.