|

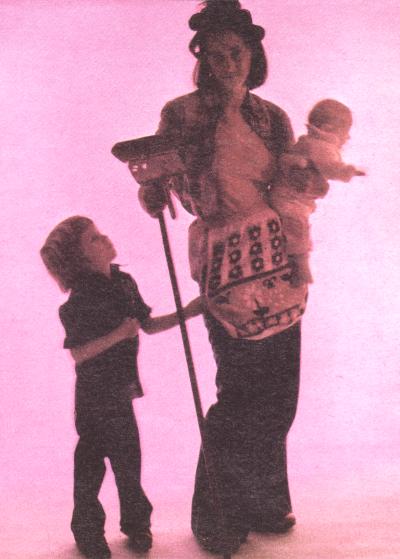

Mothering is generally a well-respected

and rewarding job, but few realize

just how much it has in common with

the other helping professions.

|

Motherhood is a demanding, rewarding profession. Nobody — teacher, preacher, psychologist — gets the same chance to mold human minds and nurture human bodies and emotions like a mother. It can be a tremendously satisfying Job, and the results of truly competent mothering can reverberate down through the generations.

But mothers, like other professionals, are prone to certain occupational hazards — Not just dishpan hands, either, but the same kind of difficulties that plague other workers such as doctors, lawyers, and psychiatrists.

One such hazard that has come to light lately is a phenomenon known as "professional burnout." Social workers, psychologists, ministers — those who deal with people intimately and intensely day after day — may after a period of months or years experience a common syndrome. The people and their problems finally "get to them." and cause them to go into a negative pattern of behavior — known as "burnout."

Symptoms may include a widening emotional detachment from their patients or clients, a loss of love and concern for them as total human beings, unwarranted anger or emotional outbursts, and various stress-related physical and mental difficulties.

But this phenomenon is not strictly limited to the "helping" professions. It can affect anybody who has to deal with people day after day without a break. And while motherhood does not normally include working with a case load of 300 clients or a group of patients who habitually call for advice at 3 a.m., it does at times mean a super intense relationship with one or more small human beings who may call for service twenty-four hours a day. And it's amazing how many mothers exhibit exactly the same behavior other professionals do when confronted with too many "people" demands.

Smoke Signals

For instance, tired professionals may distance themselves emotionally by various methods from those they serve. Doctors, for example, may refer to patients as "appendectomies" or "coronaries" instead of thinking of them as total human beings. Social workers may avoid involvement by withholding eye contact. They may minimize physical contact by using various body-language barriers like desks or counters. They may stand beside doors with their hand on the knob, ready to escape if things become too intense. Those who work with low-income families may begin to think of their clients in demeaning terms, blaming clients for their plights, instead of empathizing as they did when they first went to work in the field. Pros on the verge of a burnout may find themselves lecturing or shouting at clients for no logical reason — and perhaps they are normally kind people who would never think of behaving this way.

Motherly Parallels

A burnt-out mother may exhibit many of the same symptoms. Instead of dealing with each of her children as an individual, she may refuse eye contact. She may answer questions with a mumble or a grunt, busying herself with household tasks that emotionally exclude her offspring. She may avoid touching, hugging or other forms of body contact for lengthy periods of time. And she may mention "the kids" in the same lone of voice another pro would refer to a "case load" or "docket."

When she had her first child, she probably was intensely aware of him or her as a unique, precious individual. But time and routine may have taken a toll. The emotional stress of constantly dealing with a tiny human being who makes noise, messes, and is continually underfoot may have caused a gradual change to take place. Perhaps the arrival of one or two brothers or sisters took away the novelty and added to the load.

Like a lawyer described by Dr. Christina Maslach, she may one day find herself screaming at her young "clients" for no good reason except she has reached the end of her emotional rope ("Burned-Out." Human Behavior, September 1976. p.16). Or she may hold in her frustration until it begins to exhibit itself as the "housewife syndrome." Described by sociologist Dr. Jesse Barnard, symptoms can include nervousness, inertia, insomnia, trembling hands, nightmares, perspiring, fainting, headaches, dizziness and heart palpitation — all with no physical or pathological explanation. Burnt-out professionals like policemen, psychiatrists, and prison guards experience the same deterioration in their health, and the list of symptoms is remarkably similar: insomnia, ulcers, migraine, perspiration, nervousness, and painful muscular tension.

Mothers of small children have been known to say things like, "It's not that I can't do what I want — I can read a book, I can listen to a record. It's just that I can never do it when I want to" (Shirley L. Radi, Mother's Day Is Over, p. 190). Psychiatrists who have gone from hospital to private practice report experiencing the same feelings. They have difficulty finding time for a little peace and quiet alone, because there's nobody else to go on duty for them when the shift is over. One minister complained of the same imposition on his "down time" at home: "I hate to hear the phone ring — I'm afraid of who it's going to be and what they'll want."

Dr. Maslach noted that for social workers the biggest sign of burnout was that a creative person with original thoughts and a fresh approach to the job found himself transformed into a "mechanical bureaucrat." This is also a signal of motherly burnout. One woman reported listening to her neighbor in an adjacent apartment scream "No!" to her active toddler over and over again in the course of a morning. Apparently all imagination (give the child some unbreakable goodies to play with; take him for a walk: read him a story) had vanished before the need to be a good bureaucrat (get the housework done immediately at any cost).

Burnt-out psychologists may resort to cutting down the time of therapy sessions with clients. Burnt-out mothers send the kids outside for lengthening periods of time.

The parallels are endless.

What Causes Burnout?

Our society has yet to take a straight, honest, collective look at motherhood and see it for what it is — a tremendously rewarding, but also tremendously demanding job that can provide immense satisfactions but sometimes exacts a terrific toll.

Marriage is a fantastic opportunity for growth, and children give parents an even greater opportunity to grow and develop. But growth is sometimes, perhaps more often than not, a painful process. A young woman should be thoroughly prepared for the sacrifice, the self-denial, the total giving that's required of a mother before she ever says "I do." She needs to be a thoroughly mature person who "has her head on straight," so to speak. She should have lived, experienced, studied, worked, traveled enough to know what it means to give these things up for a certain number of years to become the willing servant of one or more small emotionally and physically demanding human beings.

Young women may delude themselves into thinking they're prepared for this giant step when they definitely are not. They may have bought the fairy tale of Prince Charming as the answer to all their frustrations, when in actuality this "happy ending" will only aggravate their problems. Marriage is not for immature people — and neither is parenthood.

Women who have married with this dream firmly in mind may be unable to give it up long after the honeymoon is over. Not ever having been presented with an honest alternative to this world's false concept of marriage and family life, they compare their reality with the media mirage and feel a vague or not-so-vague dissatisfaction, but can't really put their finger on the cause. Perhaps they blame themselves, their husbands, their income, their mother-in-law, or some other factor for their unhappy situation.

But the real problem may be that they are unable to level with themselves as to the real nature of their jobs. When they find out motherhood isn't all fluffy pink dresses, talcum powder and pleasant moments in a rocking chair, they may not know how to handle it — and they may become prime candidates for burnout.