Europe and Japan are tied to oil from the Middle East — an area fraught with tension.

What might occur if Middle East nations or the Soviet Union prevent precious oil from reaching either Europe or Japan?

OIL MAKES the world go round.

And since oil makes the world go round, a few not-so powerful nations could literally stop the world. How? By shutting down oil wells, blowing up pipelines, stopping tankers from delivering their oil-filled hulks to customers.

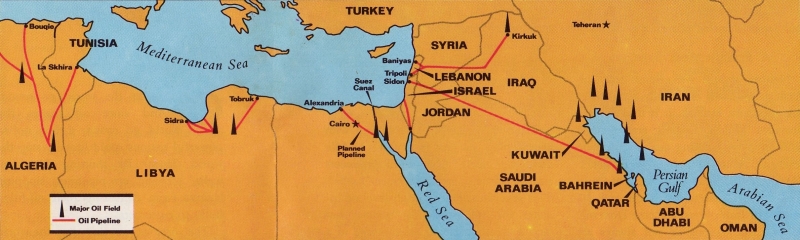

The nations in this stop-the-world drama are, in alphabetical order: Abu Dhabi, Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Syria and a few desert sheikdoms. Some of these nations perch atop multiple billions of barrels of oil or sit astride the access routes to the oil glutted countries.

Vital Middle East Oil

Although the Middle East is important to the United States because of massive U.S. overseas oil holdings, it is not a matter of industrial life or death. Only three or four percent of America's oil requirements come from that area. The massive U.S. industrial machine can override any oil blackmail or blockage.

This, with other factors, could lead to American disinterest in the Middle East — an attitude which could result in fatal consequences for the area.

But friends and allies — Europeans and Japanese — cannot take the situation so lightly. To Europe and Japan, the thought of a Middle East oil stoppage brings a thousand and one Arabian nightmares.

Middle East oil literally turns the wheels of European and Japanese industry. Japan imports 90 percent of its oil from the Middle East; Britain relies on the Middle East and North Africa for 70 percent of its oil needs; France 80 percent; West Germany close to 90 percent; Italy almost 95 percent.

As a whole, 85 percent of Western Europe's oil is extracted from beneath the desert floors of the Middle East and North Africa. Libya supplies about one third of Western Europe's oil needs. She is Britain's most important supplier. Algerian oil supplies are earmarked for France.

The impact of these statistics is obvious. Western Europe's prospects for industrial growth are directly linked to a continuing and unimpeded access to Middle East oil. If another outbreak of fighting, or some other political factor stimulates Arab oil producers or transit nations to new embargoes, the very future of the Common Market could stand in jeopardy.

You can be sure Europeans will not take such a dangerous situation with a shrug of the shoulders.

Economy Tied to Oil

Like it or not, Europeans are hooked on oil. Nuclear energy production has fallen way behind schedule. While natural gas is entering the field, coal production is running down. Coal's share of the energy market has fallen from 56 to 27 percent in ten years. Oil's share has doubled from 32 to 60 percent.

In spite of new oil discoveries such as the one-million-barrel-per-day production of Nigeria and Indonesia, oil consumption is rising out of sight. European and Japanese customers are as dependent on the Middle East oil as they ever were. There can be no cutting of the umbilical cord between the two. Middle East and North African oil, the industrial lifeblood of Europe and Japan, must continue to flow.

Western Europe, with a population of 354 million people, is guzzling oil and the full range of oil products — gasoline, jet fuels, fuel oils, lubricants — at the voracious rate of 12 million barrels each day.

This is three times their consumption of ten years ago. Predictions, notoriously shortsighted, say that the need for oil will double by 1980.

Japan is also a prisoner of oil. Even in 1958, Japan was the world's seventh largest oil consumer. She has gradually but steadily climbed the list since then. Besides, Japan has no present promise of large natural gas supplies which Europe hopes to count on. Japan's existing nuclear power industry is still too fledgling to make any appreciable dents in her energy needs.

Japan must be nurtured on oil if she is to grow 15 percent annually in her GNP and become Dai Ichi — "Number One" by 2000 A.D. Japan already burns 3.4 million barrels of oil per day, and is forecast to consume over 10 million in 1980. After that, it's anyone's guess.

Yet, oil-poor Japan must presently rely on the Middle East for anywhere from 85 to 93 percent of her oil — depending on who is doing the counting.

Clearly, oil requirements put Japan in a very vulnerable economic and military position.

What of the Future?

In the light of Japan's and Europe's oil vulnerability, the particularly annoying questions are: Will Middle East and North African oil flow unimpeded in the 1970's and 1980's? If oil flow is slowed or blocked simultaneously by a consortium of nations, what, will be the reaction of both Europe and Japan? Would either Japan or Europe (or both) forcibly intervene militarily in the affairs of the obstructing nations to uncork the flow?

Is the growing influence of the Soviet Union in the Middle East a threat to industrial development and stability of Western nations? Could a world war result over restricted oil supply?

Some of these questions may seem farfetched to those unacquainted with the importance of oil. But these are real dilemmas faced by European and Japanese statesmen who must deal with the realities of Middle Eastern, North African and Soviet politics.

Oil is a massive industry. It is the single most important item in world trade. Yet, the greatest possibilities for growth in the industry still lie in the future. A few simple statistics show why. By 1950 twice as much crude oil was produced as in 1945. Ten years later production again doubled to 1,000 million tons. By 1968, the amount produced had again doubled. The prospect (almost always too conservative) is for oil production to double once again by 1980.

Therefore, an oil crisis alone could lead to war in the Middle East. Today, the United States alone is providing a peace-keeping balance of power in the area. But suppose the United States should make the gross political blunder of eliminating itself from the Middle East arena? An Armageddon could result.

|

|

Middle East Oil Production

|

|

SAUDI ARABIA

LIBYA

IRAQ

ABU DHABI

QATAR

TUNISIA

|

1.17 billion barrels annually

1.13 billion barrels annually

552 million barrels annually

215 million barrels annually

130 million barrels annually

29 million barrels annually

|

IRAN

KUWAIT

ALGERIA

OMAN

EGYPT

BAHREIN

|

1.23 billion barrels annually

940 million barrels annually

346 million barrels annually

131 million barrels annually

89 million barrels annually

28 million barrels annually

|

Oil Sparks a World War?

In order to portray graphically how political events surrounding an oil stoppage could lead to a war involving many powerful nations, consider the following fictitious, but wholly possible scenario of the future:

It is November, 1977. Winter is coming on and Europe has increased fuel needs.

A federation of Middle East nations called the United Arab Union has been involved in months of stormy haggling over oil prices. They now decide to put the squeeze on the foreign-owned oil companies and their paying customers, hoping to increase revenues. The nations in the federation are Egypt, Libya, Syria, Sudan, Algeria and South Yemen.

Syria takes the first step. Army personnel blow up the Tapline and other pipelines carrying oil from Saudi Arabian and Iraqi oil fields. Simultaneously, Egypt closes its supertanker pipeline from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. Libya and Algeria, supplying a good share of the oil needs of Germany and France, shut down their wells. Oil flowing to Europe from west of the Suez Canal has been effectively halted.

More importantly the Soviet Union, seeing a resurgent Europe on its Western border and a mighty Chinese-Japanese combine on its Eastern flank, makes its now-or-never move.

The Soviet Union, secretly backing the United Arab Union oil embargo, uses its bases on both sides of the Strait of Hormuz to blockade any oil leaving Iraq, Iran and other sheikdoms. It moves troops into South Yemen at the request of the Arab states. From its Socotra base in the Indian Ocean, Saudi Arabia and the east end of the Red Sea are blockaded. All this is done in defiance to political hand-slapping by the U.S. As a result of Soviet actions, no oil can leave the area.

Europe's Panicky Reaction Europe and Japan are in turmoil. Worried leaders quickly assemble to assess the options open to them.

Industrial leaders pressure their governments to get oil flowing immediately. "Unless it does," they say, "reserves will soon run out, wrecking Europe's industries." The public is up in arms. Soon there will be fuel rationing and higher prices. In time, as fuel runs out, transportation will grind to a halt. The job market will be catastrophically affected.

But diplomatic talks are having no effect. The United Nations, as usual, is powerless to act. The Soviet Union has just vetoed consideration of the problem in the Security Council. Public, industrial and economic pressure increases to the breaking point.

In secret, the ten Common Market nations agree that the only road to survival is an invasion of the Middle East and the seizure of oil sources and transit points.

As a result, European troops — part of the military arm of the Common Market — make three simultaneous invasions. From friendly Israel, European troops smash across the delta region of Egypt. Objectives? Open the Suez Canal and the Alexandria pipeline, then roll across Egypt and invade Libya. From the west, European troops land in Tunisia. Their object is to conquer Algeria and link up with troops fighting west across Libya and to reopen these vital oil sources.

At the same time, the European Navy is furiously making its way through the Suez Canal to reopen the Red Sea shipping lanes and break the Soviet Union's Indian Ocean blockade.

They also hope to link up with Japanese naval vessels attempting to smash their way through the Straits of Malacca into the Indian Ocean from the East.

To support this action, troops strike south through Egypt, the Sudan and Ethiopia.