Unnatural Breeds

Men have imposed upon their livestock many limitations that God did not impose at creation. They look around and see what our animals are now like and assume they are the best ever — thinking we are evolving better and better all the time.

Many Britons, Australians and Americans feel: "It has to be bigger — or have greater capacity — to be better," and have disregarded all other factors in preference for capacity production in all types of livestock. Then they adamantly insist they have increased the quality of their product. But what is the result of this "improvement"?

A few years ago a high concentration of nitrates in forage crops in Missouri, Illinois, and Wisconsin poisoned and killed many hundreds of cattle. Dr. Arthur A. Case, M.S., D.V.M., Professor of Veterinary Medicine, University of Missouri, reported on this tragedy in the Haver Glover Messenger: "In most instances, by the fifth day several of the largest and best cows were found either dead or very sick. Almost all of the sick animals were dead in 24 hours." Notice that the largest and supposedly best cows — the most "improved" individuals — succumbed first, because they had the lowest resistance to poison. The gain in size had been a loss in hardiness. The human body, fed by these inadequate animals, is reaping the same results.

In recent years most dairymen have had a mania for increasing the size of their cows in order to further increase individual production, and have assumed that increasing the size also increases the strength. Their newest technique in choosing herd cows is to use wither height only as their guide to quality. Now these dairymen are wondering why these abnormally larger cows are suddenly having difficulty giving normal birth, whereas their smaller ancestors fifteen years ago gave birth without distress.

Many dairymen claim a bigger cow gives proportionately more nourishment in her extra gallons of milk. But milk tests have proved that this increased capacity does not give a proportionate increase in the nourishment — that the increase is practically all water, which the dairyman then sells to the customers at milk prices.

Men claim that cattle were originally scrubs and had to be bred for capacity. But this is not true. God created good livestock, not scrubs (Gen. 1:24-27). In ancient times when God's people were taken into captivity and a few poor people were temporarily left in the land, a large family was able to get an abundance of milk and butter from one young cow and two sheep (Isa. 7:21-22).

Laying hens are even more distorted than cattle. The modern egg has a pale, flat, sick-looking yolk and a watery white that splatters all over the skillet — with the flavor missing! Such an egg is not remotely comparable to that produced by a non-pressured hen in a back-yard flock — with its rich, flavorful yolk and firm, healthy white.

Does this mean selective breeding is wrong? Most assuredly not! It only means selective breeding has been misapplied, wrongly used.

God saw fit to preserve in the Bible the example of the patriarch Jacob's selective breeding technique. Scholars recognize that Jacob had an amazing amount of knowledge and skill in livestock breeding.

Jacob agreed to herd Laban's cattle and take as his pay all the odd-colored animals, while the standard colors were to be Laban's (Gen. 30:27-34). Because Laban changed Jacob's wage frequently in order to enrich himself with Jacob's labor (Gen. 31:7), God performed a miracle to cause the animals to produce a fair wage for Jacob, as described in verses 6-12.

The account makes it obvious that Jacob bred for strength as regards hardiness, vigor, and virility, which perpetuates quality in general. In his quest for quality, he trusted God to provide the quantity in the right color patterns. Jacob did not fix a particular color pattern or other unnatural characteristic by incest as modern breeders have done, but left hereditary qualities as they were. He picked the most virile males, corralled them for breeding with the more virile females in order to produce quality — and as a result God rewarded him with a decent wage (Gen. 30:37-39, 41-43 and 31:38).

As a constant safeguard against inbreeding, Jacob maintained a flock ratio of one male to ten females (Gen. 32:13-14). Modern authorities unwisely recommend one male to thirty or forty females — or one male to thousands of females in artificial insemination, admittedly a calculated risk!

Dr. C.O. Gilmore of the Ohio Experiment Station, in a report in The Rural New Yorker, stated that artificial insemination has already begun to produce many heritable defects that are becoming a public concern. With 90% of our dairy cows now being artificially inseminated, a few more years of such a practice could lead to sudden degeneration of entire herds.

Men have departed from God's way and in their greed have bred their cattle and poultry for isolated characteristics according to man's desire for each particular breed: excessive fat; blocky, big-rumped frames; excessively rapid growth; abnormal amounts of milk and eggs, unusual or unnatural color patterns, and other hereditary distortions.

The present livestock crisis of disease, dwarfism and birth difficulty — is abundant proof that modern breeders have been wrong in their judging of what constitutes quality, and what is profitable, in the long run, for human health. Then why were bad breeding practices introduced in the first place? What did these men want to accomplish?

Bakewell and his followers lived in England's fertile valleys that had attracted settlers with varied sorts of cattle. The cattle had been allowed to promiscuously crossbreed until the land was full of mongrels.

Bakewell thought the way to improve those cattle was to take local individuals that looked good and, through incestuous mating, develop a new, supposedly superior, breed by concentrating on developing certain desired characteristics. He and his followers did not generally consider going to other areas and buying good quality pure breeds for foundation stock.

The practice temporarily worked so well that some tried it on pure breeds to increase the size, milk capacity, or fattening ability. As farmers were paid for quantity, their reasoning easily told them quantity meant quality! What actually happened was that quality was sacrificed for quantity — all in the name of quick profits.

But in other areas good breeds of pure cattle were not changed by this system. Their owners were satisfied with the natural and just profit their stock produced. These breeds, though profitable, were neglected by Bakewell and his followers because they were either too small or they were in areas far removed from the productive plains and valleys that inspired the use of Bakewell's system.

These neglected natural breeds have generally retained their natural hardiness since creation. They do not suffer the losses from disease, dwarfism, and birth difficulties so common in the artificial breeds. This fact and their superior digestion make them generally as profitable as the artificial breeds. They produce meat and milk — or eggs in the case of poultry — that are of noticeably superior quality. The meat of the old, natural breeds, according to all authoritative comment, is not tough and stringy as some have assumed. It is tender and well marbled without heavy layers of waste fat, is of superior flavor, and very highly prized by the consumer. These breeds have rugged constitutions, but tender meat. Men who switch from new breeds to the old breeds are always surprised at their many good qualities.

Quality Breeding

The natural breeds came from areas where conditions were rugged and farmers could not afford to use a breeding technique that caused a loss of hardiness and quality. They left their cattle as God created them. And in many cases owners of these natural breeds have been "old-fashioned" enough to be honest — to recognize, and strive for, true quality in livestock. The meat of natural breeds does not have to be artificially tenderized as the unnatural breeds usually require. Corruption is a chain reaction: one sinful practice requires another, and then another, to cover up. Now the whole land is full of the wretched result of such actions. The ultimate result is our own sickly bodies.

To better understand the qualities all cattle should have by nature, notice the traits of some of the natural breeds which have been bred for over-all quality and hardiness, instead of for one or two isolated characteristics. The best market beeves of the natural breeds — such as Scotch Highlanders, Brahmans, Galloways, Dexters, Red Polls, and Charolais — can be counted on to dress out a carcass weighing 58% to 64% of live weight with very little or no waste fat! But the artificial breeds dress out no more than 60% to 65% of live weight — only a very little more, and have a considerable amount of waste fat, and many times have a considerable amount of hard, unmarbled lean. The evidence amply demonstrates that the natural breeds actually produce a higher percentage of lean beef, and that of better quality and flavor. It is a widely known fact that the natural beef breeds give their calves a better supply of rich milk than most cows in the artificial beef breeds.

|

Natural breeds do not have to be finished on the feedlot: they are good and tender fresh out of the pasture — and grass is much less expensive than grain. When put in the feedlot, the natural breeds put on tender lean, instead of waste fat.

In regard to commercial milk production, Mr. Sanders and others inform us the old, natural breeds such as Dexters, Red Polls, and Kerries have long been noted for both quality and richness of milk, and for profitable production. At the Model Dairy contest conducted at Buffalo in 1901, a Red Poll cow placed second in individual competition for profitable production. All the Red Polls entered were from one herd, but in most other breeds, contestants were picked from numerous herds scattered all over the country. Thus, the first place winner, a Guernsey, had a decided advantage (The Taurine World, pp. 683-684). Red Polls, though still not numerous, have won many similar dairying honors since that time.

Another ancient breed is the Irish Dexter, smaller than a Jersey but almost as beefy proportioned as an Aberdeen Angus. Big-cow enthusiasts who look with contempt on the Dexter's small size have to ignore several vital factors which prove it does not have to be bigger to be better. They are such good foragers they eat young bushes and dry cornstalks from top to bottom — which increases their health and profitableness. Even though tiny, they give up to three gallons of very rich milk a day. Those who have raised these tiny cows many years affirm that "they produce both milk and beef more economically than the strictly beef or dairy breeds."

|

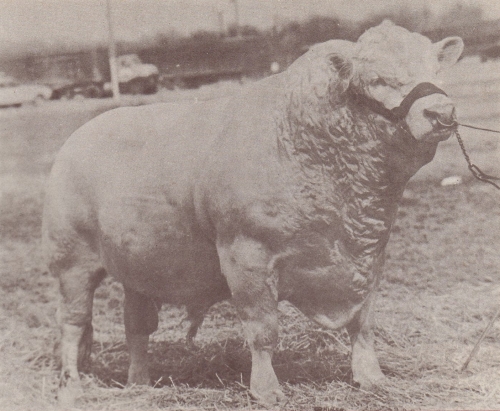

American-International Charolais Assn.

Huge Charolais cattle, because they have been normally bred and are large by natural

heredity, have none of the dwarfism associated with the three major beef breeds

mentioned in the previous installment. The Charolais are not bothered by pinkeye,

which plagues most other light-skinned breeds. Note the bulging muscles,

which indicate much lean meat and very little waste fat.

|

Dexters are so gentle and affectionate it is not uncommon to have children do the milking and feeding — even caring for the bulls (which I have personally witnessed). Some families actually give Dexters the dog's place as household pet. But this does not make them delicate: Dexters can take extremes of heat and cold without discomfort. In England, where most other dairy cattle are put in snug barns in winter, Dexters are commonly housed in sheds open on three sides, without loss of production. Even though short legged, they are so agile on foot that steep, rocky terrain offers no problem. (The Dexter Cow, by W.R. Thrower)

These factors of hardiness, which are common — in slightly varying degrees — to all the old, natural, pure breeds, whether large or small, contribute greatly to their profit-making capacity. When exposed to wintry cold, any of the hardy breeds get a better start in the spring and are not adversely affected by sudden spring storms.

People who are familiar with only the artificial breeds assume that the natural breeds are just as limited and just as adversely affected by distresses. But this is not true. The natural breeds consider such things as sudden weather changes to be normal. Scotch Highlanders, for example, are not, as some suppose, just northern cows. They are so adaptable they do not appear to suffer from the heat of Southern California summers. Big, gentle Brahman cattle, assumed to be suited only for hot climates, adapt more readily to Canadian winters than the light dairy breeds, and frequently spend their time in the open in below-zero weather, even when a barn is available — according to reports from northern breeders.

Charolais cattle, another big, extremely gentle breed, are noted for hardiness, for milk that tests up to six per cent butterfat, and for fine quality, tender beef. Having long been bred in France for hardiness and lean meat, these cattle did not have their nature distorted in the interest of unnatural profit.

The ancient, natural beef breeds are usually better milkers than the artificial breeds. Brahmans are sometimes used as family milk cows because of their abundance of rich milk that tests over five percent butterfat. Devon cattle are such heavy milkers that they used to be considered dual-purpose cattle. Some writers still list them as such, although the Devon Cattle Club lists them as strictly beef cattle.