The beginning of the Sanhedrin, the origin of the "traditions of the elders,"

the usurpation of authority by laymen — these are discussed in this installment.

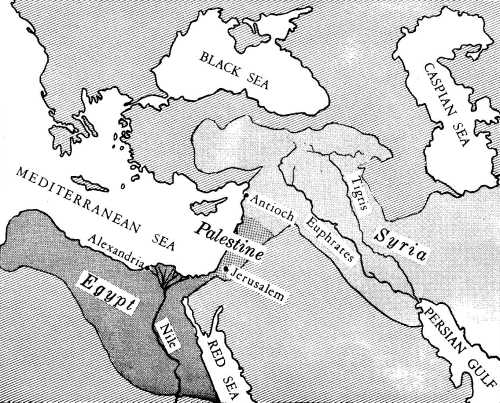

IN previous installments we followed the Egyptian rule of Palestine until 198 B.C. In that year the Syrian kingdom on the north invaded and conquered the territory of Judea. The change in government from Alexandria to Antioch in Syria — and the resultant establishment of the Syrian way of life in Palestine — meant that a readjustment had to be made in the Jews' manner of living inherited from the Egyptian Hellenists.

The Syrians were Hellenists as much as the Egyptians were but there was quite a difference in their mode of observing it!

The Religious Anarchy Ends

When the Syrians assumed control of Palestine, the Jews were fully conscious that something new was taking place. It was this contrast between the Egyptian Hellenism they had been used to and the Syrian Hellenism which they were now obliged to follow, that shocked a few Jews into becoming-cognizant that another way of life was possible — their old way of life — living by the Holy Scriptures! The Jews knew the Scriptures plainly did not recognize either form of Hellenism. New interest in God and the religion of Moses began to revive.

Beginning of Sanhedrin

This new interest in the religion of their forefathers caused some of the Jews to reflect on the past in order to ascertain how their forefathers had been governed in their religious life. They recognized that from the time of Ezra and Nehemiah to Alexander the Great, the Sopherim had been the religious leaders and teachers of the people. The Sopherim, remember, had disappeared from the scene — Simon the Just was the last of them.

Understanding that some organization like the Sopherim must exist if there was to be religious unity and the people properly taught the Law, the leaders of this new revival decided to meet in council with one another. Its avowed purpose was to direct those who were desiring to live according to the Law of their forefathers. This council became known by the Greek name, THE SANHEDRIN.

It is not clear when the Sanhedrin first began meeting. It must have been just a short time after the Syrians came into Palestine, perhaps about 196 B.C. or immediately thereafter (Lauterbach, Rabbinic Essays, p. 207).

The influence of the Sanhedrin was not great at first. Not many of the Jews recognized its authority or adhered to its injunctions. Yet, with its establishment, we can say that outright religious anarchy came to an end, even though the majority of the Jews were still greatly affected by Hellenism.

Fanatical Zeal of Syrian Hellenists

When the Syrians subdued the Egyptians in Palestine in 198 B.C., they brought to the Jews their own ideas concerning Hellenism. To the Syrians there must be nothing that rivaled their way of thinking.

Egyptian Hellenists had allowed the Old Testament to be used. The interpretation of it, however, must be by Greek methods — it had to be Grecianized. Thus, we have the Septuagint Version. But the Syrian Hellenists would not allow the Old Testament even to be in existence. Only Greek ways were allowed. No form of individual or nationalistic religion was allowed to exist that conflicted in any way with the doctrines of the Syrians.

A map of Palestine during the time of Hellenistic influence.

Ambassador College Art Department

|

The outstanding advocate of this philosophy was the Syrian king, Antiochus Epiphanes, who ruled from 175 to 164 B.C.

Antiochus Epiphanes was a Hellenist enthusiast, proud of his Athenian citizenship and bent on spreading Hellenic civilization throughout his domains. He built various temples to Apollo and Jupiter. He observed, and commanded his subjects to observe, all the pagan Greek festivities to the heathen gods. So fanatical was he in his zeal to implant his beliefs on all others that some of his contemporaries called him HALF-CRAZED (Margolis, History of the Jewish People, p. 135). He let nothing hinder him from realizing his desires.

A large number of the Jews readily accepted the newly established Syrian doctrine of complete surrender to the philosophies of Hellenism. Most of the Jews were thoroughly accustomed to much of the Greek culture anyway, and it was no hard thing to transfer allegiance from the Egyptians to the Syrians.

Yet, by the time of Antiochus Epiphanes, other Jews had also begun to take a new interest in religion — the religion of their forefathers. This new concern for religion was beginning to spread among the Jews of Palestine.

|

When Antiochus Epiphanes heard that some of the Jews were rejecting his doctrines of total adherence to Hellenism, he began to persecute many of them. The persecution inevitably caused more Jews to side with the cause of religion. This stubbornness of the Jews infuriated Antiochus. He then began — in a fit of demoniac insanity — widespread persecution, committing heinous indignities against all those who would not conform to his ways.

Not all the Jews were in disfavor with Antiochus. Many of the wealthy and influential families, and especially many of the chief priests, wickedly supported Antiochus in his wild schemes. As the persecution grew more intense, a great many of the common people went against Antiochus. The result of this unparalleled persecution by this madman inevitably brought a further quickening interest in the Scriptures. Many began to take up arms against the Syrians. The cry went throughout the land that, in reality, this was a religious war and that the Jews were fighting for their Law and their God. This belief boosted renewed interest in fighting against Antiochus. See part6 of this series for a detailed description of the atrocities that made Antiochus so hated by the Jews.

Judas Maccabee

The Jews, in order to band themselves together against the Syrians, came to the side of Judas Maccabee and his four brothers. An army was formed for two purposes: 1) defeating Antiochus Epiphanes and 2) driving out the Syrians from Palestine. This army was quickly put into action. After many successful battles, in succeeding decades, this Jewish army managed to accomplish both things! Antiochus' armies were defeated in 165 B.C. and by 142 B.C. the Syrians were completely driven from the land. Practical independence for the Jews resulted.

Religious Authority Re-established Among Jews

With the defeat of Antiochus Epiphanes in 165 B.C., the religious history of the Jews enters a new phase. The Sanhedrin, which had been feebly established some thirty years before, was now officially declared the religious authority among the Jews of Palestine. Being in virtual control of the land, the Jews were in position to re-establish the religion that had been in a state of decay for so long.

Now, for the first time since the period of the Sopherim, they had independent religious authority. The Sanhedrin tookthe place of the Sopherim in directing the religious life of the people. But, this governing body of men was to be greatly different from the priestly Sopherim.

During the period of religious anarchy before Antiochus Epiphanes, a fundamental change took place in the attitudes of the priests. Many of the priests were outright Hellenists and steeped in the pagan philosophies of that culture. Not only that, many of them had sided with Antiochus Epiphanes against the common people during the Maccabean Revolt. Such activities caused the common people to be wary of the priests and their teaching. There was a general distrust for anything priestly at this time.

A few priests had not allied themselves with Hellenism and Antiochus Epiphanes. But the large majority, in one way or another, were not faithful to the religion of their forefathers.

This general lack of trust for the priests led most of the common people to disapprove of their re-assuming their full former role of being religious authorities. Only those priests who had not been openly in favor of Hellenism were sought and allowed to take their former positions. The common people could not bring themselves to entrust the other priests with the right to help regulate the religious life of the Jews. Only to these faithful priests were committed chairs in the new Sanhedrin (Lauterbach, Rabbinic Essays, p. 209).

Non-Priestly Teachers Assume Authoritative Positions

Under Egyptian control, within the period of the religious anarchy, Palestine had no official teachers of the Law. A few individuals here and there endeavored to study the Scriptures in a personal way. Without official teachers, the study obviously had to be personal and in private. The fact that a few independent students of the Law existed is proved by the few learned men who came to the fore with the establishment of a Sanhedrin. We are further assured of this when we realize that this new Sanhedrin, organized about 196 B.C., was composed of LAY TEACHERS as well as some priests.

"The study of the Law now became a matter of private piety, and as such was not limited to the priests" (Lauterbach, Rabbinic Essays, p. 198).

This private study, without proper guidance from recognized authority such as the Sopherim were, brought about some surprising results.

(This is the same condition that happened in the Protestant Reformation. Many lay teachers arose, because the Bible was made available by the printing press, and many confusing and contradictory divisions arose amongst those who were coming out of the Catholic Church)

Many of these Jewish teachers, likewise, because of their independent private study in the Scripture, were not in unity on many of their teachings. And, too, many of these teachers were variously affected by Hellenism.

"We shall therefore be not far from the truth if we represent the Sanhedrin, in the years from its foundation down to the outbreak of the Maccabean Revolt, as an Assembly of priests and laymen, some of whom inclined to Hellenism while others opposed it out of loyalty to the Torah" (Herford, The Pharisees, p. 27).

The differing degrees of Hellenic absorption among the teachers, mixed with independent study of the Scripture, brought about a new variety of opinions. And, in the discussions that followed to determine which opinions to use, the LAY TEACHERS claimed as much right to voice their views as the priests. The lay teachers were assured of the common people being behind them.

"At the beginning of the second century these non-priestly teachers already exerted a great influence in the community and began persistently to claim for themselves, as teachers of the Law, the same authority which, till then, the priests exclusively had enjoyed" (Lauterbach, Rabbinic Essays, p. 28).

Such privileges that the lay teachers were usurping to themselves would never have been permitted while the Sopherim, the successors of Ezra and Nehemiah, were in authority. The Law of Moses, which God had directly commanded him, clearly enjoined that the priests, with their helpers the Levites, were to perform the functions of teachers, not just any layman who would presume to do so.

Some of these priests were in the Sanhedrin and were willing to re-establish the religious life of the people, in accordance with the directions in the Law. But the new laymen, who had now also become teachers of the Law because of their independent study, were not willing to give up this new power they had acquired. Human reason insisted that they were as competent to teach the people as the priests.

Lay Teachers Reject Sole Authority of Priests to Teach!

When the Sanhedrin was re-organized after Antiochus Epiphanes, the lay teachers exhibited more power than ever before. The priests, who were under a ban of discredit before the Maccabean Revolt, were even more so afterwards. The lay teachers repudiated the claim that the priests had an exclusive right to be in authority.

Lauterbach says that these lay teachers "refused to recognize the authority of the priests as a class, and, inasmuch as many of the priests had proven unfaithful guardians of the Law, they would not entrust to them the religious life of the people" (Rabbinic Essays, p. 209).

This privilege, of assuming the role of the priests, was not a complete usurpation of every prerogative of the priests. They still were the only ones allowed to perform the ritualistic Temple services, etc. No lay teacher ever thought of taking over this exclusive position of the priests.

But from the time of the re-establishment of the Sanhedrin, after the Maccabean Revolt, the lay teachers became the important religious leaders.