It was my first visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

I was standing before The Last Judgment,

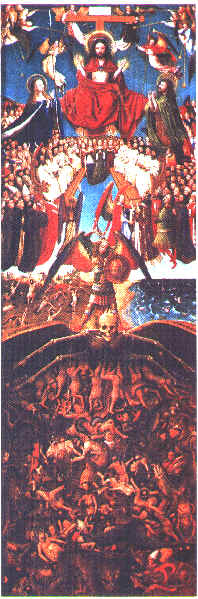

a painting by the 15th-century Dutch artist Jan van Eyck.

The words, large and in quotes,

were intended as an alternate

title for the painting.

They were chilling in their impact:

"The Case Against Christianity"

|

On the floor, directly in front of the painting, lay a sheet of paper bearing a few hastily written words. An earlier visitor had placed it there, and it had not yet been removed by museum personnel. The words, large and in quotes, were intended as an alternate title for the painting. They were chilling in their impact: "The Case Against Christianity." They stopped me cold. What had prompted the visitor to level such a charge? I took a closer look at the painting. At the top of the canvas, in heaven, sits an impassive Jesus, surrounded by a host of angels and an adoring multitude of the saved. At the bottom, in hell, is a writhing mass of the damned, suffering brutal torture at the hands of hideous demons.

The contrast between the rather prim majesty of heaven and the harrowing nightmare of hell is Striking. And — as the note-writing visitor had intended — it poignantly frames an age-old question:

How can the concept of eternal Suffering in hell be reconciled with a God of mercy and love?

For many, this is indeed a case against Christianity. They want noticing to do with a Christian God who could sit back and watch his children roast for eternity in a subterranean chamber of horrors. A deity of such Cruelty and vindictiveness, they feel, could not be the true God.

Hot Debate

Non-Christians are not the only ones who have problems with the idea of hell. Hell is one of the hottest debates within the Christian community today.

Most Christians believe in hell as the fate of those who reject God. but one Christian's idea of hell may not be another's.

While most Christians agree that the essence of hell is separation from God, the in-house debate is over the specifics — where hell is, when it is, how hot it is and how long it is.

Why? Because the Bible offers little detail. Hell is a doctrine about which there is no clear and dogmatic teaching in Scripture. The interpretation of biblical statements and the imagery they employ is beset with difficulties.

As hell appears to be a harsh doctrine, many Christians today choose to explain it in ways that soften its impact. The modern trend has been to replace the traditional fire and brimstone concept of hell as a place of eternal torture with a more politically correct portrayal of hell as a condition of spiritual anguish caused by separation from God. In other words, hell is not a place but a state.

|

Polls reveal that while nearly two-thirds of Americans believe there is a hell, the majority of them think of it as a state of existence or a condition rather than a literal blazing underworld.

Likewise, growing numbers of Christian scholars are speaking out against what they regard as the folly of relying on purely literalist readings of scriptural statements about the sufferings of the damned. They object to interpretive methods that fail to recognize the textual context, the literary genre of the passages, their historical setting and the broader theological context of Christ's saving work and God's love for humanity.

Conservatives, on the other hand, denounce as revisionists those who advocate a more figurative view of hell. In watering down the reality of painful retribution in an eternal fiery hell, these liberals are undermining an important biblical doctrine, conservatives believe.

Not a Core Doctrine

Though some portray the issue of hell as central, history tells another story.

The doctrine of hell evolved long after the core doctrines of the historic Christian faith were established. The views of the early Church fathers about hell were far from unanimous. It took the Christian community hundreds of years to come up with a consensus on the issue. The majority view — that hell is a place of eternal fiery torment — emerged only after a long debate within the Church.

By the Middle Ages, the concept of a fiery underworld had become a dominant element in people's minds. To the medieval faithful, hell was a place of suffering and despair, of wretchedness and excruciating pain.

The medieval Church used fire-and-brimstone rhetoric to its fullest to keep believers under control. The Church considered hell a useful prod to piety, a strong incentive to refrain from evil.

The Inferno

Though criticism was raised by some churchmen against the over dramatization of hell, the brutal imagery of medieval theology tended toward ever-more-vivid portrayals of hell's horrors. And nowhere were those horrors so dramatically depicted as in The Inferno, the first part of The Divine Comedy, an epic poem by the Italian author Dante Alighieri (1265-1321).

The Inferno records Dante's imaginary travels among the damned. His purpose was to warn his readers that reward or punishment would surely meet them hereafter.

According to Dante, hell is divided into nine rings or circles, descending conically into the earth. Within this multi-leveled chamber of horrors, souls suffer punishments appropriate to their sins. Gluttons, for example, are doomed to forever lie like pigs in a foul-smelling sty under a cold, eternal rain of filth and refuse. The lustful — driven by their passions during this lifetime — are forever whirled about in a dark, stormy wind.

Although the fruit of Dante's fertile imagination, The Inferno is generally in keeping with the theology of his age. His picture of hell as a gigantic concentration camp — a nightmarish place of eternal torment presided over by Satan — became fixed in the popular imagination. It continues to represent the thinking of some Christians to this day and of some critics of Christianity who mistakenly assume that Dante's frightful imagery comes from the Bible.